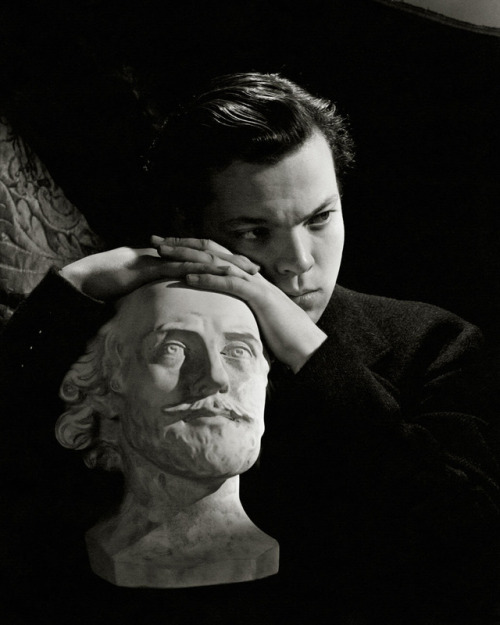

Aos dez anos, a inteligência de Orson

era notícia de jornal. Aos treze, ele interpretava a Virgem Maria em uma peça

da escola. Aos 19, ele dirigiu sua primeira peça. Aos 23, sua performance de “Guerra

dos Mundos” no rádio chocou Nova York. Aos 26, ele dirigiu e protagonizou um

dos melhores filmes já feitos. E então ele tomou um choque de realidade.

Hollywood não estava preparada para Orson Welles – então ele levou sua mágica

para outros lugares e outras telas. Seu início brilhante, sua demissão a jato e

os posteriores altos e baixos de sua carreira fazem de Welles um assunto

perfeito para um documentário.

At age ten, Orson’s intelligence was highlighted in

a newspaper note. At age 13, he was playing the Virgin Mary in a school play. At

age 19, he directed his first play. At age 23, his radio performance of “War of

the Worlds” shook New York. At age 26, he directed and starred in one of the

best films ever made. And then reality struck. Hollywood wasn’t ready for Orson

Welles – so he took his magic to other places and other screens. His brilliant

start, his quick demise and all the subsequent ups and downs in his career make

Welles a perfect subject for a documentary.

Welles vai de “garoto prodígio” a “forasteiro”

a “cigano”, depois toma “o caminho de volta” até se tornar “o mestre”. Estes

são os títulos dados aos cinco capítulos do documentário “Magician: The

Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles”. Eu já escrevi sobre como eu me vejo

em Orson Welles, e por que ser uma criança prodígio é ao mesmo tempo uma bênção

e uma maldição. Se minha vida realmente espelha a dele, o documentário me

mostrou o que virá a seguir para mim – mesmo eu, aos 26 anos, ainda não tendo

criado meu “Cidadão Kane”.

Welles goes from being a “wonder boy” to an

“outsider” to a “gypsy” to catching “the road back” until he becomes “the

master”. These are the titles given to the five chapters of the documentary “Magician:

The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles”. I’ve written before about how I

see myself in Orson Welles, and why being a child prodigy is at the same time a

blessing and a curse. If my life really mirrors his, the documentary showed me

what I can expect next – even if I’m 26 and haven’t made my “Citizen Kane” yet.

A mãe de Orson acreditava que uma

criança precisava ser interessante para poder socializar com os adultos. E não

havia ninguém mais interessante que o pequeno Orson: ainda criança ele era

pianista, autor, poeta, cartunista, conhecedor de diversos assuntos, de

Shakespeare à China. Orson perdeu a mãe quando tinha nove anos, e alguns anos

depois ele foi para um internato, onde ninguém conseguiu impor limites a ele.

Formado aos 16 anos, ele logo se tornou estrela de uma peça, mesmo sendo seu

primeiro papel, e depois começou a dirigir peças, se tornando o maior diretor

de teatro experimental dos Estados Unidos antes de completar 25 anos.

Orson’s mother believed a child needed to be

interesting in order to be able to socialize with the adults. And there was

nobody more interesting than little Orson: as a kid he was a piano player,

author, poet, cartoonist, well versed in several subjects, from Shakespeare to

China. Orson lost his mother when he was nine, and a few years later he went to

boarding school, where nobody was able to establish limits for him. Graduated

at 16, he quickly became the star of a play in his very first acting job, and

then started directing plays as well, becoming the greatest experimental

theater director in the US before he turned 25.

É interessante ver as reações à

famosa performance de rádio de “Guerra dos Mundos” num domingo de 1938. Muitas

cartas chegaram à estação de rádio, algumas delas parabenizando Welles for sua

criatividade e pela diversão que ele propiciou, enquanto outras condenavam seu

ato, chamando-o de “desumano” e irresponsável por causa do pânico que a

brincadeira causou. Felizmente, houve mais consequências positivas do que

negativas, como o próprio Orson notou: “Eu não fui para a cadeia. Eu fui para Hollywood.”

It’s interesting to see the reactions to the

infamous “War of the Worlds” radio performance on a Sunday evening in 1938.

Many letters arrived at the radio station, some of them congratulating Welles

for his creativity and for the fun he provided, while others condemned his act,

calling him “inhuman” and irresponsible because of the panic the prank caused.

Fortunately, there were more positive consequences than negative ones, as Orson

himself said: “I didn’t go to jail. I went to Hollywood.”

O primeiro projeto em que Welles

tentou trabalhar foi em uma adaptação de “Heart of Darkness”, que se provou

impossível por muitas razões, entre elas a censura do Código Hays... e o fato

de a RKO querer trabalhar com figurantes em blackface. Essa não foi a única vez

em que a RKO atrapalhou os planos de Welles: mesmo dando carta branca para ele

fazer “Cidadão Kane”, o estúdio mutilou sua obra-prima seguinte, “Soberba”,

para tornar o filme mais curto, e o estúdio o demitiu de sua missão documental

na América do Sul depois que os executivos viram que ele havia “filmado muitos

negros” no Brasil.

The first project Welles tried to do in Hollywood

was directing an adaptation of “Heart of Darkness”, which proved impossible for

many factors, including Hays Code censorship... and RKO wanting to work with

extras on blackface. This wasn’t the only time RKO messed up with Welles: even

though they gave him free reign for “Citizen Kane”, they mutilated his next

masterpiece, “The Magnificent Ambersons”, in order to make it shorter, and

fired him from his documental mission in South America after seeing that he had

“filmed too many black people” in Brazil.

Welles trouxe sua técnica

experimental para Hollywood. Como um diretor de cinema novato – “O primeiro dia

em que dirigi um filme foi o primeiro dia em que pisei num estúdio de cinema” –

ele sabia muito pouco sobre convenções e técnicas e, provavelmente sem querer,

ele desafiou e quebrou essas convenções, criando uma obra-prima arrebatadora.

Surpreendentemente, anos mais tarde, Welles confessou que acreditava que “Rosebud”

não era um bom elemento da trama.

Welles brought his experimental approach to art to

Hollywood. As a newcomer film director – “The first day I directed a film was

the first day I’d ever been in a movie set” –he knew little about screen

conventions and, probably without wanting to do so, he defied and broke these

conventions, creating a riveting masterpiece. Surprisingly, later in life

Welles confessed he thought “Rosebud” wasn’t a good device for the plot.

Em todos os outros filmes em que ele

trabalhou como ator nos anos 1940, Welles também trabalhou um pouco como

diretor – e nunca foi creditado. Nos anos 1950, Orson deixou Hollywood porque

estava sendo investigado pelo FBI – as pessoas acreditavam que ele poderia ser

um “comunista”. Na Europa, ele trabalhou sobretudo de forma independente.

In all the other films he appeared in the 1940s as

an actor, Welles also worked a bit as a director – and always went uncredited. In

the 1950s, Orson left Hollywood as he was being investigated by the FBI –

people believed he could be a “communist”. In Europe, he worked mostly as an

independent filmmaker.

Orson foi incompreendido em um lugar

onde os diretores raramente tinham controle sobre seus filmes, e teve de

enfrentar problemas financeiros para completar a maior parte de seus filmes,

levando anos para terminar cada projeto. Para conseguir dinheiro para seus filmes,

ele aceitava papéis em produções para o cinema e a TV, alguns deles bem

curiosos – por exemplo, quem haveria de pensar em juntar Welles com os Muppets?

Orson was misunderstood in a place where directors

rarely had control over their films, and struggled financially to complete most

of his movies, taking years to finish each project. In order to make money for

his films, he would accept parts in movies and television, some of them pretty

weird – I mean, who would have thought of putting Welles with The Muppets?

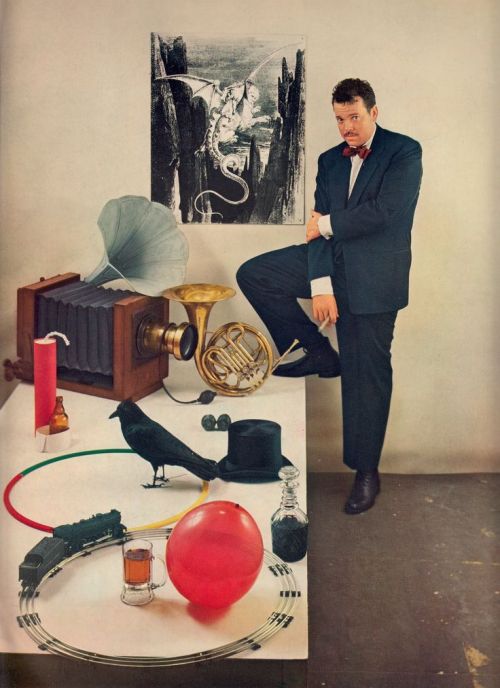

Assim como a maioria dos perfeccionistas,

Orson Welles deixou muitos projetos inacabados, como o conhecido projeto “Don

Quixote” e “O Outro Lado do Vento”, que foi finalmente lançado em 2018. Welles

faleceu em 1985, enquanto trabalhava em, por incrível que pareça, um programa

de TV sobre um mágico – ele se interessara por ilusionismo ainda na infância e

mostrou muitos truques em “Verdades e Mentiras” (1973).

Like most perfectionists, Orson Welles left many

unfinished projects, like the well known “Don Quijote” project and “The OtherSide of the Wind”, that was finally released in 2018. Welles died in 1985,

while he was working, of all things, on a TV show about a magician – he had

been interested in illusionism from an early age, and showed many tricks in “F

for Fake” (1973).

O documentário usa imagens de

arquivo, cartazes de teatro, recortes de jornais, entrevistas e muito mais para

pintar um retrato completo de Orson. No meio deste material está a primeira

experiência de Orson com uma câmera, em um curta-metragem que ele e sua

companhia de teatro fizeram por diversão no começo dos anos 1930.

The documentary uses archive footage, theater

posters, newspaper prints, past interviews and more to build a complete portrait

of Orson. Among the material, there is Orson’s first experience with the

camera, in a short film he and his theater company shot for fun in the early

1930s.

Partes de conversas com Oja Kodar, a última

companheira de Welles, são reveladoras, como quando ela diz que Orson teria

sido o homem mais feliz do mundo se Geraldine Fitzgerald – Oja se refere a ela

como “Geraldine qualquer-que-seja-o-nome” – tivesse confirmado que Orson era

pai do filho dela, Michael Lindsay-Hogg – pelo menos a semelhança é inegável.

Ela também conta que viu Orson assistindo a “Soberba” no fim da vida e

chorando, ainda ressentido com o resultado final.

Little bits of conversation with Oja Kodar,

Welles’s last companion, are revealing, as she says Orson would have been the

happiest man in the if Geraldine Fitzgerald – Oja refers to her as “Geraldine

whatever-her-name-is” – had confirmed that her son Michael Lindsay-Hogg was

Orson’s son – at least the resemblance is uncanny. She also tells that she witnessed

Orson watching “The Magnificent Ambersons” late in life and crying, still angry

at the final film.

A atriz Jeanne Moreau define Welles

como “um rei destituído” – pois não havia reino no mundo bom o suficiente para

ele. Já que o documentário diz – e eu concordo – que Orson era um homem à

frente de seu tempo, a definição de Jeanne está correta: o reino que deveria

ser governado por Welles ainda não existia quando ele estava vivo. Eu me

pergunto que truques e experimentos ele faria hoje, com as mídias digitais.

Actress Jeanne Moreau defines Welles as “a

destitute king” – as there was no kingdom in the world good enough for him.

Since the documentary says – and I agree – that Orson was a man ahead of his

time, Jeanne’s definition is correct: the kingdom Welles was meant to reign

over didn’t exist yet when he was alive. I wonder what tricks and experiments

he would have made today, with digital media.

No final, se você já sabe um bocado

sobre Orson Welles, o documentário não traz nada de novo, e seu título termina

sendo mais impressionante que o próprio documentário. Mas é um bom filme para

os iniciantes que acabam de começar a desvendar Orson, esta figura gigantesca

em muitos sentidos.

In the end, if you already know a good amount about

Orson Welles, the documentary doesn’t bring anything new, and its title ends up

being more astonishing than the documentary itself. But it is a good movie for

beginners who have just started learning about Orson, this larger-than-life figure

in many senses.

This is my contribution to the Some Kind of a Man: the Orson Welles blogathon, hosted by Sean Munger.

He does sound an interesting character Le, thanks for this review as a newbie to his work this looks like a good place to start. I've only seen him in wee roles and some of the adverts I reviewed.

ReplyDelete