Os dois escritores mais famosos de Portugal são

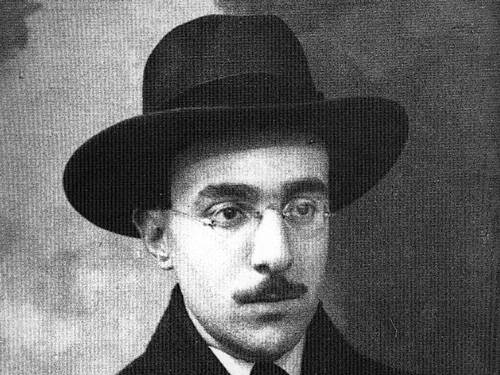

o romancista José Saramago – que inclusive ganhou o Nobel – e o poeta Fernando

Pessoa. Enquanto Saramago chegou a Hollywood com a adaptação paras as telas de

seu livro “Ensaio Sobre a Cegueira” em 2008 – curiosamente dirigido pelo

diretor brasileiro Fernando Meirelles – Pessoa nunca chegou a Hollywood. De

acordo com o IMDb, seus escritos serviram de base para 36 produções, a maioria

curtas-metragens. Mas o próprio Pessoa já havia sonhado em conquistar as telas.

The two

most famous writers from Portugal are novelist José Saramago – who is also a

Nobel laureate – and poet Fernando Pessoa. While Saramago made it to Hollywood

when his novel “Ensaio Sobre a Cegueira” (Essay on Blindness) was adapted for

the screen as the film “Blindness” (2008) – curiously directed by Brazilian

director Fernando Meirelles – Pessoa never made it to Hollywood. According to

IMDb, his writings were the base for 36 productions, most of them shorts. But

Pessoa himself once dreamed about reaching the screen.

É importante dizer que Fernando Pessoa não era

só um: ele era múltiplo. Ele criou diversos heterônimos para escrever em

estilos diferentes e sobre assuntos diversos – e até criou biografias para

eles. Um destes heterônimos era Álvaro de Campos, um poeta futurista,

engenheiro e quase sempre um homem amargo. Em seu poema “Carnaval” ele diz:

“Fitas de cinema correndo sempre / E nunca tendo um sentido preciso”. Álvaro de

Campos criticava tudo, incluindo o cinema.

It’s important to say that Fernando Pessoa

wasn’t just one: he was multiple. He created several alter egos / heteronyms to write in

different styles and about different subjects – and even created biographies

for them. One of these alter egos was Álvaro de Campos, a futuristic poet, an

engineer and almost always a bitter man. In his poem “Carnaval” he says: “Film

reels always running / And never having a precise sense”. Álvaro

de Campos criticized everything, including cinema.

Mas o próprio Fernando Pessoa pensava que o

cinema poderia ser muito útil para promover Portugal em terras estrangeiras.

Então, o que ele fez? Ele planejou abrir uma companhia cinematográfica! Seu

empreendimento, que seria chamado Cosmopolis, produziria filmes especiais de

propaganda, mostrando o melhor lado do moderno e agora democrático país que era

Portugal – o país se tornou uma república em 1910, abandonando o regime

monárquico.

But

Fernando Pessoa himself thought that cinema could be very useful to promote

Portugal in foreign lands. So, what did he do? He planned to open a film

company! His endeavor, to be called Cosmopolis, would produce special

propaganda films, showing the best side of the modern and now democratic

Portugal – the country became a republic in 1910, abandoning the monarchic

government.

O plano da Cosmopolis foi feito no final da

década de 1910 e logo abandonado. Mas Pessoa voltou nos anos 20 com uma nova

ideia: uma produtora de cinema a ser chamada de Ecce Film, que teria sua sede

na famosa Rua de São Bento, 333-335, onde muitos filmes já haviam sido feitos.

Este empreendimento também não se realizou. Mas Pessoa não se importou, pois em

meados dos anos 1920 ele estava escrevendo argumentos para o cinema.

The

Cosmopolis plan was made in the late 1910s and soon abandoned. But Pessoa came

back in the 1920s with a new idea: a film production company to be called Ecce

Film, and to have its headquarters at the famed São Bento Street, 333-335,

where many films had been shot. This endeavor also didn’t become true. But

Pessoa didn’t care, as in the mid-1920s he was actually writing film arguments.

Os sete argumentos que Fernando Pessoa escreveu

foram mantidos em segredo por quase 80 anos, e em 2011 eles foram reunidos no

livro “Argumentos para Filmes” pelos pesquisadores Patricio Ferrari e Claudia

Fischer. Pessoa escreveu os argumentos em português (apenas os diálogos), inglês

e francês, e estes textos podem ser divididos em duas categorias: thrillers

(cinco deles) e comédias (os outros dois).

The

seven arguments Fernando Pessoa wrote were kept a secret for nearly eighty

years, and in 2011 they were reunited in the book “Argumentos para Filmes”

(that is, Movie Scripts), by researchers Patricio Ferrari and Claudia Fischer. Pessoa

wrote the arguments in Portuguese (dialogues only), English and French, and

these texts can be divided in two categories: thrillers (five of them) and

comedies (the other two).

Um argumento, intitulado “Três Andares”,

demonstraria as desigualdades sociais através de três famílias de um mesmo

prédio, mas de diferentes classes sociais, que executam a mesma ação. Um

thriller inclusive apresenta o uso do MacGuffin: neste filme, um milionário

cruzaria o Atlântico de navio levando consigo um objeto valioso e acompanhado

por um detetive particular, e então várias pessoas tentariam roubar este

objeto... apenas para descobrir no final que o objeto real já havia sido

enviado em outro navio na semana anterior.

One

argument, called “Three Floors”, would demonstrate social inequalities by

having three families from the same building but from different social classes

do the same actions. One thriller even has a clever use of the MacGuffin: in

this film, a millionaire would cross the Atlantic by ship taking a valuable

object with him and accompanied by a private detective, then several people try

to steal this object... only to find out in the end that the real object had

been shipped a week earlier in another ship.

|

| Lisbon in the 1920s |

É também interessante notar que Pessoa escreveu,

em 1930: “Com exceção dos alemães e dos russos, ninguém ainda colocou nada de

arte no cinema”. Ele parece refletir aqui a opinião de outros escritores portugueses

que escreviam e publicavam a revista Presença e geralmente davam destaque aos

filmes alemães e soviéticos. Embora Pessoa criticasse os “homens vazios do

cinema”, comparando Mary Pickford e Rodolfo Valentino a aventureiros tolos que

apenas queriam quebrar recordes de velocidade (ele usa as palavras “viciados em

velocidade, estrelas de papelão do cinema”), uma revista com anotações

encontrada em seus pertences mostra que ele estava particularmente interessado

no mapa astral de Joan Crawford.

It’s

also interesting to see that Pessoa wrote, in 1930: “Except the Germans and the

Russians, no one has as yet been able to put anything like art into the

cinema”. He seems to reflect here the opinion of fellow Portuguese writers who

wrote and published the magazine Presença (Presence) and often highlighted

German and Soviet films. Although Pessoa criticized the “film hollow men” of

Hollywood, comparing Mary Pickford and Rudolf Valentino to silly adventurers

who only wanted to break speed records (he uses the words “speed dopers, film

cardboarders”), an annotated magazine found in his belongings shows that he was

particularly interested in Joan Crawford’s astrology chart.

Fernando Pessoa faleceu em 1935 aos 47 anos –

por causa de cirrose ou pancreatite. Ele deixou muitos trabalhos e

empreendimentos inacabados, incluindo todos estes mencionados na seara do

cinema. Companhia cinematográfica, produtora de filmes, argumentos fílmicos: é

bastante coisa para alguém que escreveu, em uma carta de 1929 para o amigo José

Régio: “Ao inquérito sobre cinema não responderei. Não sei o que penso do

cinema.”

Fernando Pessoa passed away in 1935 at age 47 –

due to either cirrhosis or pancreatitis. He left many works and endeavors unfinished, including

all these mentioned in the film world. Film company, production company, seven

arguments: it’s a lot for someone who wrote, in a 1929 letter to his friend

José Régio: “I won’t answer the questionnaire about cinema. I don’t

know what I think about cinema.”

|

| "Como Fernando Pessoa Salvou Portugal" (2018) |

Fontes:

FERRARI, Patricio. FISCHER, Claudia. Fernando

Pessoa: Argumentos para Filmes. Lisboa: Editora Ática, 192 p, 2011.

MARTONI. Alex Sandro. O cinema de Fernando Pessoa. Cadernos de Letras da UFF - Dossiê: Palavra & Imagem n° 44, p. 393-398, 2012.

SANTIAGO, Silviano. Fernando Pessoa e o cinema. Estado de São Paulo, 09 de junho de 2012.

This is my contribution to the Luso World Cinema Blogathon, hosted by Beth and me at Spellbound by Movies and here at Crítica Retrô.

Has a movie been made about this man? He would make an interesting study. I also liked what he said about not knowing what he thinks about cinema. That's quite a statement!

ReplyDeleteFun that he was movie mad like the rest of us, but he was a bit coy at the end. I am sure he had opinions of cinema since he did in the past. The part about Joan Crawford's astrology made me giggle!

ReplyDelete