Dois

críticos de cinema entram em um bar. Eles jamais chegam a um acordo sobre qual

drink pedir. Por quê? Porque crítica cinematográfica não é algo unânime, pois a

paixão sempre influencia quando um crítico está analisando um filme. Esta piada

pode não ser engraçada, mas é verdadeira: dois críticos de cinema, mesmo

parceiros na profissão, dificilmente têm a mesma opinião sobre um filme. Tome

como exemplo a dupla Roger Ebert e Gene Siskel. Nos mais de 20 anos em que eles

fizeram listas anuais dos 10 Melhores Filmes lançados, eles concordaram em

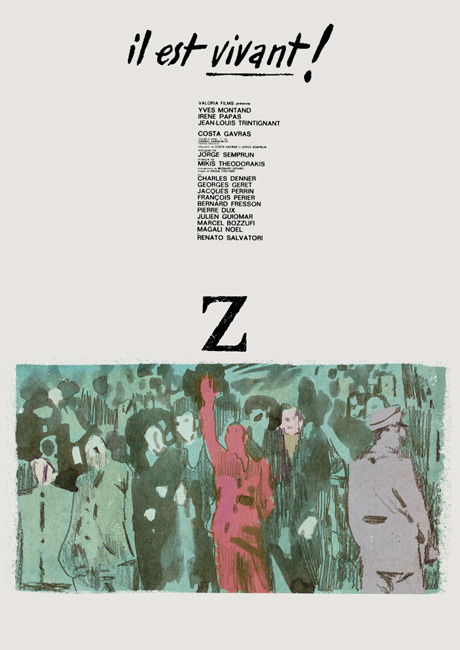

poucas ocasiões. Uma delas foi quando ambos elegeram, em 1969, o filme Z de

Costa-Gavras como o melhor do ano.

Two film critics walk into a bar. They never

agree on which drink to order. Why? Because film criticism is not meant to be a

unanimous thing, since passion weighs in whenever a critic is analyzing a film.

This joke may not be funny, but it’s true: two film critics, even in a

partnership, rarely agree on their opinions about film. Take the duo Roger

Ebert and Gene Siskel, for instance. In the more than 20 years they made their yearly

TOP 10 movies, they rarely agreed on the best film of the year. One of these

occasions was in 1969, when both favored Costa-Gavras’ Z.

Z é um

thriller político que me mostrou como lutas políticas vêm em ciclos. Z é um

famoso político grego e líder de um partido de esquerda. Ele é interpretado por

Yves Montand. Uma noite, o discurso de Z para o povo francês é quase cancelado

– ele quer falar sobre paz, e contra ele estão o governo francês, a polícia, a

imprensa e muitas pessoas raivosas. Depois do final do discurso, realizado em

um local diferente do planejado, Z é atacado por um homem com um cassetete. A

polícia se desespera com a possibilidade de o crime se tornar uma questão

política – e, de fato, foi um crime político – e por isso a Gendarme – a

polícia francesa – tenta encobrir o crime e fazer ele passar por acidente.

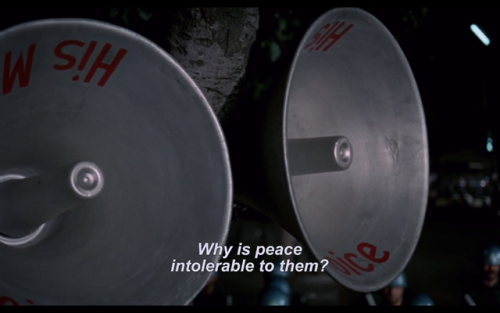

Z is a political thriller that showed me how

political struggles come in cycles. Z is a prominent Greek politician and

leader of a leftist party. He’s played by Yves Montand. One night, Z’s speech

to the French people is almost cancelled – he wants to talk about peace, and

against him there is the French government, the police, the press and a lot of

angry people. After the speech ends, in a different location than planned, Z is

attacked by a man with a nightstick. The police is then nervous with the

possibility of the crime becoming a political issue – and it really was a

political crime – so the Gendarme – the French police – try to uncover the

crime and label it an accident.

Z é baseado

em uma história real, e você precisa saber um bocado de história para entender

melhor o filme. A história contada envolve o assassinato do político grego

Grigoris Lambrakis por uma milícia de direita em 1963. Quando ficou provado que

Grigoris foi assassinado, o resultado esperado era a vitória do partido de

esquerda nas eleições... mas não houve eleições: em 1967 um golpe de estado

aconteceu, e a Grécia se tornou uma ditadura de extrema-direita. Este governo

proibiu muitas coisas, entre elas cabelos compridos, a minissaia, Tolstoi,

Sófocles, greves, os Beatles, liberdade de imprensa e a letra Z – uma letra

que, em grego, significa “ele vive”.

Z is based on a real story, and you need to

know a bit of history to better understand the film. The story told involves

the assassination of Greek politician Grigoris Lambrakis by a right-wing

militia in 1963. When it was proved that Grigoris was murdered, the result was

an expected win of the left parties in the elections… but there were no

elections: in 1967 a coup d’état happened, and Greece became a right-wing

military dictatorship. This government prohibited a lot of things, including long

hair, mini-skirts, Tolstoi, Sophocles, strikes, the Beatles, freedom of press

and the letter Z – a letter that means “he’s alive” in Greek.

Há alguns

indícios de que o assunto é política grega. O mais óbvio de todos vem da trilha

sonora, composta por Mikos Theodorakis, cuja obra foi proibida pela ditadura

militar. O diretor Costa-Gavras nasceu na Grécia, assim como a atriz Irene

Papas, que interpreta a esposa de Z. E, para tornar tudo mais explícito,

Costa-Gavras colocou este aviso no começo do filme: “Qualquer semelhança com

eventos reais, com pessoas vivas ou mortas, não é mero acaso. É PROPOSITAL.”

You get a few hints that we’re talking about

Greece. The most obvious one comes from the soundtrack, composed by Mikis

Theodorakis, whose work was banned by the military dictatorship. Director

Costa-Gavras was born in Greece, just like actress Irene Papas, who plays Z's

wife. And, to make things even more explicit, Costa-Gavras puts this warning in

the beginning of the film: “Any resemblance to actual events, to persons living

or dead, is not the result of chance. It's DELIBERATE.”

Como o

governo norte-americano apoiava a ditadura grega, o filme Z foi quase banido

nos EUA. Em vez disso, algo pior aconteceu: todas as pessoas que compraram

entradas para assistir a Z tinham seus dados pessoais anotados pelo FBI – um usuário do IMDb escreveu sobre como isso aconteceu com ele. Além disso,

Costa-Gavras, Theodorakis, Irene Papas e Yves Montand foram proibidos de entrar

nos EUA nos anos seguintes.

Since the US government supported the Greek

dictatorship, the film Z was nearly banned in the US. Instead, something worse

happened: all people who bought tickets to see Z had their personal data taken

by the FBI – one IMDb user writes about how it happened to him. Moreover,

Costa-Gavras, Theodorakis, Irene Papas and Yves Montand were forbidden from

entering the US in the following years.

Gene Siskel

escreveu sobre Z: “É um grande filme por muitas razões, podendo ser apreciado

como um thriller político ou uma declaração política.” Por outro lado, Roger

Ebert escreveu: “É um filme da nossa época. É sobre como até as vitórias morais

são corrompidas. Ele te fará chorar e te deixará furioso. Ele

arrancará suas entranhas.” De fato, Ebert insistiu em denunciar a política que

permeia o filme – e até hoje, seis anos após sua morte, Ebert é atacado em seu

site por causa de sua crítica de Z.

Gene Siskel wrote about Z: “It is a great film

for many reasons, not the least of which is that it can be enjoyed as a

political thriller as well as a political statement.” On the other hand, Roger Ebert wrote: “It is a

film of our time. It is about how even moral victories are corrupted. It will

make you weep and will make you angry. It will tear your guts out.” Indeed,

Ebert didn’t shy away from denouncing the politics surrounding this film – and until

today, six years after his death, Ebert is attacked in his site because of his

review of Z.

Para mim, Z

teve um efeito muito pessoal. O Brasil está entre 30 a 50 anos atrasado em

relação ao resto do mundo em todas as áreas, incluindo na política. Em 2018 um

governo foi eleito prometendo “caçar comunistas” e seus apoiadores gritavam “nossa

bandeira jamais será vermelha”. O ano de 2018 no Brasil começou com o

assassinato de uma vereadora no Rio e com a prisão política de um ex-presidente

que fazia parte do maior partido de esquerda do país. Os paralelos não param

por aí. Em Z, os militares são obcecados pela “ameaça comunista” e prometem ser

anticorpos para a doença esquerdista. Este foi um discurso usado em 1964,

quando um golpe militar aconteceu no Brasil, e tal discurso ainda está em uso

hoje por um governo que já começou a censurar produções LGBT e revistas

feministas.

For me, Z struck too close to home. Brazil is

30 to 50 years behind the rest of the world in all fields, including the

political one. In 2018 a government was elected after promising “to hunt

communists” and their supporters chanted “our national flag will never be red”.

The year 2018 in Brazil started with the killing of a local politician in Rio

and with the political prison of a former president who was from the biggest

leftist party in the country. These are not the only parallels. In Z, the

military is obsessed about the “communist menace” and promises to be an

antidote to the leftist malady. This was a speech used in 1964, when a military

coup d’état happened in Brazil, and it is still used today by a government that

already started censoring LGBT productions and feminist magazines.

Há uma

piada na internet brasileira sobre como os franceses sempre se rebelam e

incendeiam carros quando alguma decisão do governo não os agrada. Os

brasileiros não fazem isso – somos muito pacíficos para lutar pelos nossos

direitos. Por bem ou por mal, os franceses tomam as ruas quando querem mudança.

Nós não. Não tomamos as ruas quando um juiz não imparcial mandou prender um

líder político popular. Não estamos tomando as ruas agora, quando o homem que

está investigando as notícias falsas espalhadas durante as eleições está

recebendo ameaças de morte. Porque nós não tomamos as ruas, estamos voltando

para 1964. Porque nós não aprendemos com a história, deixamos que a história de

nosso país seja feita de ciclos.

There is an internet joke in Brazil about how

French people always riot and burn cars when some governmental decision

displeases them. Brazilians don’t do it – we’re too peaceful to fight for our

rights. For good or for bad, French people take the streets when they want

change. We don’t. We didn’t take the streets when a judge that wasn’t impartial

arrested a popular political leader. We aren’t taking the streets now, when a

man who is investigating fake news spread during the elections is receiving death

threats. Because we don’t take the streets, we are going back to 1964. Because

we don’t learn with history, we let our national history be made of cycles.

Z não é um

filme reconfortante – na verdade, ele me afetou muito porque estou no epicentro

de toda essa confusão política. Ao final de Z, você não terá sua fé renovada. É

um filme duro sobre como política, ditaduras e golpes de estado funcionam, e é

a confirmação de que a política pode ser necessária, mas é também o campo de

batalha mais podre do mundo.

Z is not a reassuring movie – in fact, it hit

me too hard because I’m so close to all this political mess. In the end of Z,

you won’t have your faith renewed. It’s a raw film about how dictatorships,

coup d’états and politics work, and it is the confirmation that politics may be

necessary, but they also are the most rotten battlefield in the world.

This is my contribution to the Siskel & Ebert at the blogathon, hosted by Sally from 18 Cinema Lane.

1 comment:

Very interesting review! I had not heard of this movie until you told me you would be reviewing it. But it sounds like a story involving subject matter that needs to be discussed. Thanks for participating in the blogathon! I'll add your review to the participant list right away.

Post a Comment