Um conhecedor de filmes, quando ouve

“Hammer Films”, pensará em filmes de horror, como os da série do Drácula com

Peter Cushing e Christopher Lee. Eles não estão errados. Entretanto, a Hammer

Films engloba muito mais que isso: assim como qualquer estúdio de cinema, ela

teve de começar em algum lugar, e no começo a Hammer era muito diferente

daquilo que a tornou conhecida a partir dos anos 50. Para conhecer prestes

primeiros tempos, analisaremos o mais antigo filme da Hammer que ainda

sobrevive em sua versão completa: “A Canção da Liberdade” (1936).

A film connoisseur, after hearing “Hammer Films”,

will think about horror movies, like the Dracula series with Peter Cushing and

Christopher Lee. They are not wrong. However, there is more to Hammer Film:

like any movie studio, it had to start somewhere, and in the beginning Hammer

was so very different from what made it popular in the 1950s onwards. To look

at this beginning, we analyze the earliest Hammer film that fully survives:

“Song of Freedom” (1936).

É o ano de 1700 em um canto ainda não

explorado da África. Lá reina a tirana rainha Zinga, que sente prazer em

humilhar os prisioneiros antes da execução. Em uma destas terríveis cerimônias,

Zinga coloca seu medalhão real no pescoço de um homem que havia tentado tirá-la

do poder. Uma moça rouba o medalhão do pescoço dele, e foge com o filho de

Zinga. Eles chegam a uma vila e pedem ajuda para seguirem com a fuga. O único

problema é que eles pedem ajuda a um traficante de escravos.

It’s the year 1700 in a not yet explored corner of

Africa. There reigns the tyrant queen Zinga, who loves to humiliate her

prisoners before execution. In one of these horrible ceremonies, Zinga places

her royal medallion in the neck of a man who was trying to take her out of the

throne. A girl steals the royal medallion from his neck, and runs away with

Zinga’s son. They reach a village and ask for help to go further away. The only

problem is that they asked a slave trader for help.

O filho de Zinga e a moça se tornam

escravos, e uma montagem mostra que o medalhão deles passou de pai para filho

nos séculos seguintes. No ano de 1838, o tráfico de escravos acaba (exceto para

o Brasil) e os negros são libertações. Finalmente, chegamos ao tempo presente.

O mais jovem Zinga é John Zinga (Paul Robeson), um estivador que adora cantar

uma música que ele lembra da infância, e cujo sonho é voltar para sua terra, a

África, um sonho que incomoda sua esposa Ruth (Elisabeth Welch).

Zinga’s son and the girl become slaves, and a

montage shows that the medallion they had passes from father to son in the

following centuries. In the year 1838, the slave trade is over (except to

Brazil) and black people are liberated. Finally, we arrive in the present time.

The youngest Zinga is John Zinga (Paul Robeson), a dock worker who loves to

sing a song he knew since childhood, and who longs to come back to his land,

Africa, a wish that upsets his wife, Ruth (Elisabeth Welch).

Eis que chega ao porto o compositor

de óperas italiano Gabriel Donozetti (Esme Percy). Ele ouve uma voz fantástica,

mas não consegue ver quem é o cantor. Na noite seguinte, ele vai até as docas

procurar o cantor misterioso, e finalmente encontra John cantando em uma

taverna. Ele convida John para conversarem na casa dele e, apesar de a primeira

lição de treinamento não terminar muito bem, John assina um contrato com

Donozetti porque ele quer juntar dinheiro suficiente para viajar para a África.

This is when Italian opera composer Gabriel

Donozetti (Esme Percy) arrives in the harbor. He listens to a fantastic voice,

but is unable to see who is singing. The following night, he goes to the docks

looking for the mysterious singer and finally finds John singing in a tavern.

He invites John to his house and, although the first voice training session is

not very peaceful, John signs a contract with Donozetti because he wants to

earn enough money to travel to Africa.

John faz uma turnê pela Europa e

obtém grande sucesso, mas é em casa que ele obtém a resposta para seu

questionamento: depois da ópera “The Black Emperor” (cujo subtítulo é, aff, “a

negro opera”), ela canta para a plateia a canção que ele conhece desde menino,

mas cuja origem ele nunca soube. Um pesquisador tem a resposta: a música e o

medalhão vêm da ilha africana de Casanga – e assim que John chega lá, tudo

piora.

John travels Europe singing with great acclaim, but

he finds the answer for his question at home: after the opera “The Black

Emperor” (whose subtitle is, ugh, “a negro opera”) he sings to the audience the

song he knew since childhood but never knew where it comes from. A researcher

has the answer: the song and the medallion John uses point out to the African

island of Casanga - and once John arrives there, things get ugly.

O filme é surpreendentemente bem

feito, mas quando chegamos à África pela segunda vez, ficamos envergonhados. O

racismo e o imperialismo estão por toda parte. E nem tudo estava perfeito antes

disso. O mordomo de John, Monty (Robert Adams), é o negro bobo que serve apenas

de alívio cômico, um tipo que você já deve conhecer de alguns filmes que John

Ford fez nos anos 1930. Na ilha, descobrimos que um grupo de feiticeiros tomou

o poder após a morte da rainha Zinga, e dali em diante a miséria se espalhou.

Os nativos acreditam em rituais, danças e curas mágicas, e nada sabem sobre

agricultura, política, armazenamento de comida e medicina moderna.

The film is surprisingly well-done, but when we

reach the African island for the second time, we feel embarrassed. Racism and

imperialism are now everywhere. Not that all was perfect before. John’s butler,

Monty (Robert Adams) is the silly black man who exists as comic relief only,

and you might know the type from some John Ford movies of the 1930s. In the

island, we find that a bunch of witch-doctors took the power after Queen

Zinga’s death, and from then on they spread misery. The natives believe in

rituals, magic dances and cures, and know nothing of agriculture, politics,

food storage and modern medicine.

John pode ser negro, mas ele é o

homem europeu – afinal, ele nasceu em Londres – que vai levar a civilização a

estas pobres pessoas. Os africanos são retratados como não tendo nenhum

conhecimento – algo muito longe da realidade, mas um tropo comum nas histórias

contadas pelo colonizador. Pelo menos, é bom que Casanga não seja o nome de

nenhuma ilha real. Entretanto, aí vai uma curiosidade: Casanga era o nome de um

quilombo localizado em Ubatuba, no litoral de São Paulo.

John may be black, but he is the European man -

after all, he was born in London - that will bring civilization to those poor

people. The Africans are portrayed as having no knowledge - something that was

far from the truth, but it is a common trope in stories told by the colonizers.

It’s at least a good thing that Casanga is not the name of a real island.

However, here is a curious fact: Casanga was the name of a quilombo in Ubatuba,

São Paulo, Brazil - a quilombo being a community formed by slaves who ran away

from captivity.

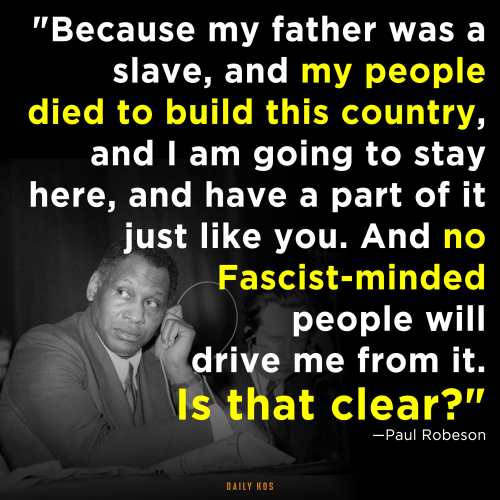

Paul Robeson me dá arrepios sempre

que canta. Robeson foi um americano que encontrou apenas preconceito em seu

país e por isso foi morar na Inglaterra. Depois de abandonar sua carreira como

advogado por causa do preconceito e ao ter dificuldades para encontrar bons

papéis para negros no cinema e no teatro americanos, Robeson foi para Londres.

Lá, ele fez sucesso em peças e filmes – foi em Londres que ele pela primeira

vez fez parte de uma montagem de “Show Boat” – e “A Canção da Liberdade” é o

filme que o deixou mais orgulhoso – porque alguns dos outros filmes estavam

cheios de racismo. Robeson deixou o cinema após uma experiência ruim em “Seis

Destinos” (1942) e mais tarde foi posto na lista negra maccarthista por ter ido

várias vezes à União Soviética e por defender a igualdade entre todos.

Paul Robeson gives me chills every time he sings.

Robeson was an American who found only prejudice in his home country and left

for England. After abandoning his career as a lawyer early on due to prejudice

and having trouble finding good parts for black men on American film and

theater, Robeson went to London. There, he was successful in several plays and

movies – it was in London that Robeson worked for the first time in the musical

“Show Boat” -, being “Song of Freedom” the one that made him the proudest -

some of the others had blatant racism. Robeson left cinema after being

discontent with his experience in “Tales of Manhattan” (1942) and he was later

blacklisted in the US due to having made several trips to Soviet Union and for

being a vocal defender of equality.

“A Canção da Liberdade” foi um grande

sucesso entre seu público-alvo: negros. Talvez eles estivessem suficientemente

felizes em ver alguém como eles na tela, sem ser ridicularizado ou torturado.

Talvez eles não tivessem minhas habilidades de historiadora que vê problema em

tudo. Não podemos negar que o filme é muito melhor que outros da mesma época –

aliás, houve algum outro filme antes desse que mostrasse o interior de um navio

negreiro? Há elementos datados, mas a presença de Paul Robeson redime todos

eles, e torna possível algo que muitos filmes modernos ainda não conseguem

fazer: dá dignidade a um protagonista negro.

“Song of Freedom” was a huge success among its

target: black people. Maybe they were happy enough to see one of theirs on

screen, not being ridiculed or tortured. Maybe they didn’t have my sharp skills

as a historian that sees trouble everywhere. We can’t deny that the film is

much better than several contemporaries – by the way, was there any other film

made before this one that shows the interior of a slave ship? There are dated

elements, but Paul Robeson’s presence redeems them all and makes possible

something many modern films are still failing to do: it gives dignity to a

black leading character.

This is my contribution to the Hammer-Amicus

blogathon, hosted by Gill at RealWeegieMidget Reviews and Barry from Cinematic Catharsis.

4 comments:

Thanks for the interesting observations about this early Hammer feature. Paul Robeson brings his inner dignity to every project, and we are fortunate that he made a number of films in England to accompany his classic recordings.

Thanks for joining the blogathon with a non-Horror and interesting post. It seems difinitely one to watch and an interesting film for this time. Great to have you onboard as always!

Thanks so much for joining the blogathon, and for writing about this important early Hammer film. I enjoyed reading about Paul Robeson, and look forward to seeing this film and some of his other roles.

I have yet to see this one! I will definitely have to check it out.

Post a Comment