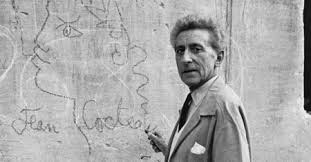

O que torna uma história um clássico? Como o diretor Jean Cocteau diz no começo de “Orfeu” (1950), uma lenda é uma história que ultrapassa as barreiras de tempo e espaço. É uma história universal, que pode acontecer em qualquer lugar, em qualquer momento, com qualquer um. O mesmo acontece com um clássico: é universal. Não importa quanto tempo se passou desde que o clássico surgiu, ele ainda mexe com a gente. E um clássico não é uma obra de arte orgulhosa: ele pode ser adaptado, mudado, subvertido – e ainda haverá uma bela história para ser contada. Esta subversão acontece com a lenda de Orfeu em “Orfeu” (1950), de Jean Cocteau.

What makes a classic? As director Jean Cocteau puts in the beginning of “Orpheus” (1950), a legend is a story beyond time and space. It’s a universal tale that can happen anywhere, anytime, with anyone. The same happens with a classic: it’s universal. No matter how long it has been since the classic appeared, it still speaks with us. And a classic is not a proud work of art either: it can be adapted, changed, subverted – and there will still be a beautiful story to be told. This subversion happens to the legend of Orpheus in Jean Cocteau’s “Orphée”, from 1950.

Orfeu (Jean Marais) é um poeta famoso. Um dia, ele

está com um amigo no Café dos Poetas quando conhece Jacques Cegeste (Edouard

Dermithe). Cegeste é um jovem poeta brilhante. Ele publicou um livro intitulado

“Nudismo”: todas as páginas estão em branco. Cegeste é bancado financeiramente

por uma mulher rica, conhecida simplesmente como A Princesa (María Casares).

Orfeu fica intrigado com Cegeste, mas não tem tempo de conhecê-lo.

Orphée (Jean Marais) is a famous poet. One day, he is hanging out with a friend at the Poets’ Café when he meets Jacques Cegeste (Edouard Dermithe). Cegeste is a brilliant new poet. He has published a book called “Nudism”: all pages are blank. Cegeste is supported financially by a rich woman, known simply as The Princess (María Casares). Orphée finds Cegeste intriguing, but has no time to get to know him.

Cegeste é atropelado por uma motocicleta em frente

ao Café dos Poetas. A Princesa o coloca no carro dela e pede que Orfeu venha

com eles para “servir de testemunha”. Orfeu os segue, e percebe que Cesgeste já

está morto. A Princesa leva o corpo de Cegeste para casa, onde ela revela sua

verdadeira identidade: ela é a Morte. Orfeu, chocado, observa a Morte e Cegeste

cruzando o limite entre a vida e a morte e desmaia.

Cegeste is run over by a

motorcycle in front of the Poets’ Café. The Princess puts him in her car and

asks Orphée to come with them “to serve as a witness”. Orphée goes with them,

and realizes Cegeste is already dead. The Princess takes Cegeste’s body to her

house, where she reveals to be… Death. A shocked Orphée sees Death and Cegeste

crossing the limit between life and death and collapses.

No dia seguinte, Orfeu é levado para casa por

Heurtebise (François Périer). A esposa de Orfeu, Eurídice (Marie Déa), está

preocupada com o desaparecimento do marido, e ansiosa para contar para ele que

ela está grávida. Orfeu não fica nem um pouco animado. Ele está agora obcecado

com uma estação de rádio peculiar que dita pequenos versos – versos melhores do

que qualquer coisa que ele já escreveu. Orfeu começa a mandar os versos que

ouviu no rádio para o jornal e isso chama a atenção do comissário local, porque

os versos são idênticos aos escritos de Cegeste, e Orfeu se torna suspeito de

matar – ou ao menos sequestrar – Cegeste

The following day, Orphée

is taken home by Heurtebise (François Périer). Orphée’s wife, Eurydice (Marie

Déa), is worried about her husband’s disappearance, and longing to tell him she

found out she’s pregnant. Orphée couldn’t be less thrilled. He is now obsessed

with a peculiar radio station that dictates little verses – verses better than

everything he ever wrote. Orphée starts sending the verses he hears on radio to

the newspaper and it calls the attention of the local commissar, because the

verses are just like Cegeste’s work, and Orphée becomes a suspect of killing –

or at least kidnapping – Cegeste.

A Morte vem para Eurídice. Orfeu se desespera com a

morte de sua esposa, e Heurtebise, que havia se apaixonado por Eurídice, decide

ajudar, contando um segredo de outro mundo: “Olhe para um espelho sua vida toda

e você verá a Morte trabalhando” – os espelhos são o que separam os vivos dos

mortos. Orfeu cruza este limite para trazer sua esposa de volta, mas descobre

que a Morte está apaixonada por ele.

Death comes for

Eurydice. Orphée becomes desperate with the death of his wife, and

Heurtebise, who had fallen in love with Eurydice, decides to help, telling an

otherworldly secret: “Look at a mirror your whole life and you’ll see Death

working” – mirror are the things that separate the living from the dead. Orphée

crosses this limit in order to bring his wife back, but finds out that Death is

in love with him.

Foi o próprio Cocteau que escreveu o roteiro,

subvertendo a antiga lenda e criando dois malfadados casais: Orfeu e a Morte e

Eurídice e Heurtebise. Cocteau também foi o narrado do filme. De certa forma,

Cocteau criou uma “trilogia de Orfeu”: três filmes baseados na lenda. “Orfeu” é

o segundo da trilogia, sendo os outros dois “Sangue de um Poeta” (1932) e “O

Testamento de Orfeu” (1960), seu último filme.

It was Cocteau himself who

wrote the screenplay, subverting the old legend and creating two doomed

couples: Orphée and Death and Eurydice and Heurtebise. Cocteau also provided

the narration. In a certain way, Cocteau built an “Orphic Trilogy”: three films

based on the legend. “Orphée” is the second of the trilogy, the other two are

“Blood of a Poet” (1932) and “Testament of Orpheus” (1960), his last film.

O compositor Georges Auric fez um excelente

trabalho em “Orfeu”, em especial na cena em que Orfeu procura a Morte em uma

rua movimentada. Auric teve uma longa carreira no cinema, começando com meu

favorito, “A Nós a

Liberdade” (1931), trabalhando várias vezes com Cocteau – como na

obra-prima “A Bela e a Fera” (1946) –, arrasando em “Rififi” (1955) e até

compondo para filmes de Hollywood como “César e Cleópatra” (1945), “A Princesa

e o Plebeu” (1953) e “Mais Uma

Vez, Adeus” (1961).

Composer Georges Auric did

a wonderful job in “Orphée”, in special in the scene in which Orphée looks for

Death in a busy street. Auric had a long career in film, starting with my

personal favorite “A Nous la Liberté” (1931), working several times

with Cocteau – like in his masterpiece “La Belle et la Bête” (1946) –, doing

great in “Rififi” (1955) and even composing for Hollywood films such as “Cesar

and Cleopatra” (1945), “Roman Holiday” (1953) and “Goodbye Again” (1961).

Nos anos 50, outra adaptação da lenda de Orfeu

apareceria e se tornaria filme em 1959: “Orfeu

Negro”, com a história ambientada no Rio de Janeiro durante o

Carnaval. Esta versão é tão interessante quanto a de Cocteau. Cocteau

conseguiu, ao recontar a história, mostrar que o amor após a morte é

complicado, e o sacrifício é necessário para atingir a felicidade em todo lugar

– até mesmo no submundo. Bravo.

In the 1950s, another

adaptation of the legend of Orpheus would appear and become a film in

1959: “Black Orpheus”, with the story set in Rio

de Janeiro during Carnaval. This version is as interesting as Cocteau’s.

Cocteau managed, with his retelling, to show that love after death is a

complicated thing, and sacrifice is necessary to be happy everywhere – even in

the underworld. Bravo.

This is my contribution to the Love Goes On blogathon, hosted by Steve at MovieMovieBlogBlog II.

No comments:

Post a Comment