Garras de Oro (1926) and the golden claws of American imperialism

Este é um

artigo sobre o filme mais enigmático do mundo. Ninguém sabe quem estava por

trás do filme “Garras de Oro”, de 1926: os atores não foram creditados, e a

equipe usou pseudônimos. O estúdio que produziu “Garras de Oro”, Cali Films,

nunca fez outro filme. Tanto mistério tem justificativa: o filme trata de uma

questão geopolítica que ainda estava fresca na mente dos colombianos, e o tom crítico

fez com que o filme fosse banidos nos EUA. “Garras de Oro” é, acima de tudo, um

filme que exemplifica perfeitamente a maneira como os EUA trataram a América

Latina no século XX.

This is an

article on the most enigmatic film in the world. Nobody knows who were the

minds behind 1926's “Garras de Oro”: the actors were uncredited, and the crew

worked under pseudonyms. The company that produced “Garras de Oro”, Cali Films,

never made another film. So much mystery is justified: the film is about a

polemic geopolitical question that was still fresh on the minds of Colombians,

and the critic tone of the film made it be banned in the US. “Garras de Oro”

is, above all, a film that perfectly exemplifies the way the US treated Latin

America in the 20th century.

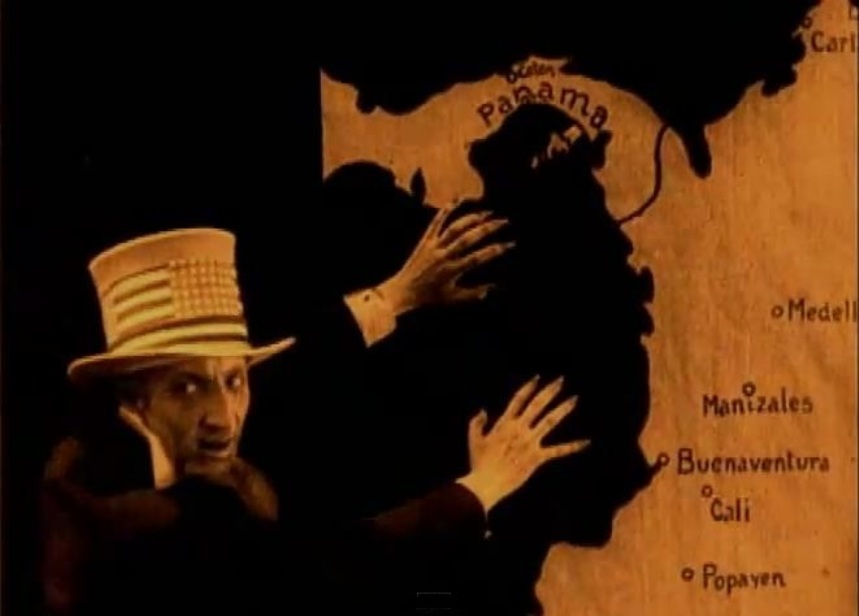

“Garras de

Oro” é ao mesmo tempo uma denúncia e uma catarse. É a história de como, em

1903, a Colômbia perdeu boa parte de seu território graças à atuação dos EUA –

e este território ficou conhecido como Panamá. Na versão dramatizada dos fatos,

os EUA são chamados de “Yanquilandia”, e os cineastas não poderiam ser mais

claros sobre o alvo de suas críticas. Teddy Roosevelt continua sendo o

presidente da Yanquilandia, e para derrotar William Taft na eleição ele decide

roubar o Panamá da Colômbia.

“Garras de Oro” (Golden Claws) is at the same time a denunciation and a

catharsis. It is the story of how, in 1903, Colombia lost a good amount of its

territory thanks to the United States – and this territory became known as

Panama. In the dramatized version of the facts, the US is called “Yanquilandia”

(Yankee Land), and the filmmakers couldn’t be clearer about who they are

criticizing. Teddy Roosevelt remains president of Yanquilandia, and to beat William

Taft in the election he decides to steal Panama from Colombia.

Em Yanquilandia há uma cidade chamada Rasca-Cielos (Arranha-Céus) e o

jornal local, chamado de The World, está contra o plano de Roosevelt. Um homem

colombiano, señor González, mora em Rasca-Cielos e tem uma filha, Berta. Ela

está apaixonada por Paterson, um americano que pode ser repórter investigativo

do The World ou mesmo espião trabalhando para Roosevelt. Corrupção, poder,

espionagem e sexo são elementos importantes na disputa geopolítica pelo Panamá.

In Yanquilandia there is a city called Rasca-Cielos (Skyscrapers) and

the local newspaper, called The World, is against Roosevelt’s plan. A Colombian

man, señor González, lives in Rasca-Cielos and has a daughter, Berta. She is in

love with Paterson, an American man who can either be an investigative reporter

for The World or a spy working for Roosevelt. Corruption, power, espionage and

sex play important roles in the geopolitical dispute for Panama.

É basicamente este o enredo de “Garras de Oro”, mas o filme era,

originalmente, muito maior: hoje apenas 55 minutos sobrevivem, e temos só uma

versão truncada do que a película era para ser – a estimativa é de que 15% do

filme ainda está perdido. Novamente, há uma explicação pra isso: banido nos

EUA, o filme foi exibido na Colômbia em 1927 e depois esquecido por 60 anos,

quando foi parcialmente redescoberto e restaurado.

That’s basically it for “Garras de Oro”, but the film was originally

much more: today only 55 minutes survive, and we have only a truncated version

of what it was meant to be – it’s estimated that 15% of the film is still lost.

Again, there is an explanation for this: the film was banned in the US,

exhibited in Colombia in 1927 and then forgotten for 60 years, when it was

partially found and restored.

No final do século XIX e início do XX, os EUA basearam sua expansão

imperialista na Doutrina Monroe – definida pelo slogan “América para os

americanos”, que na realidade queria dizer “América para os norte-americanos”.

Isso significava que os EUA apoiariam a independência dos outros países

americanos de colonizadores europeus com o único intuito de influenciar a

economia e a política destes novos países. O imperialismo norte-americano era

diferente daquele praticado pelos países europeus: era uma colonização

ideológica, não territorial.

In the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the US

based its imperialistic expansion on the Monroe Doctrine – defined by the

slogan “America for Americans”, that really meant “America for North

Americans”. This meant that the US would support the independence of other

American countries from their European colonizers with the sole purpose of

influencing these new countries in issues like economy and politics.

North-American imperialism was different from the one practiced by European

countries: it was ideological colonization, not territorial colonization.

|

| "Cowboy" Teddy Roosevelt |

O Panamá tentou se tornar independente da Colômbia em muitas ocasiões, e

finalmente houve uma guerra em 1899, chamada de Guerra dos Mil Dias – naquela época,

a Colômbia era chamada de Nova Granada. Até então, os EUA haviam ajudado a

Colômbia / Nova Granada a manter o Panamá sob sua jurisdição. Em 1903 tudo

mudou, pois o Panamá declarou independência em três de novembro, e os EUA foram

o primeiro país a reconhecer esta independência – com a clara intenção de

explorar o novo país e colocá-lo sob suas asas ideológicas. De fato, logo após reconhecer

a independência do Panamá, os EUA ganharam o controle do canal transcontinental

que seria construído no novo país. O presidente norte-americano que apoiou a

independência do Panamá foi Teddy Roosevelt.

Panama tried to become independent from Colombia several times, and they

eventually started a war in 1899, called The War of a Thousand Days – at that

time, Colombia was called Nova Granada. Up until then, the US actually had

helped Colombia / Nova Granada to keep Panama under its jurisdiction. In 1903,

things changed, as Panama declared independence on November 3rd, and the US was

the first country to recognize its independence – with the clear intention of

exploring the new country and put it under its ideological wings. Indeed, right

after recognizing Panama’s independence, the US gained control of the

trans-continental canal that would be built in the new country. The US president

who supported the independency of Panama was Teddy Roosevelt.

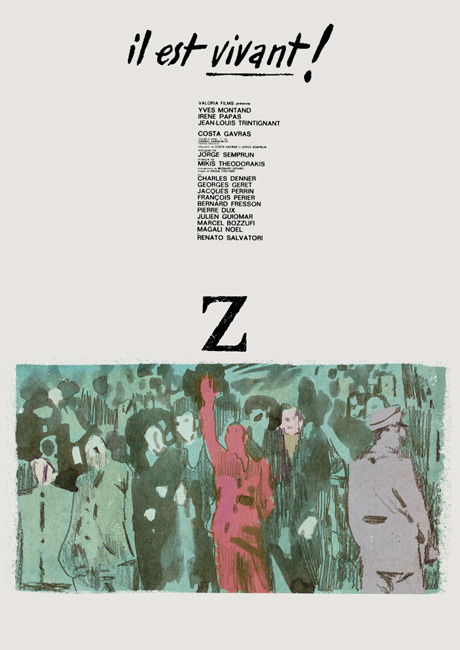

Em inglês o filme ficou conhecido como “Alvorada de Justiça” por causa

de seu conteúdo catártico – um título bem mais inofensivo do que os títulos prévios

“A Vingança da Colômbia” e “A Morte Política de Teddy Roosevelt”. Os EUA

pagaram 25 milhões de dólares como indenização para a Colômbia pelo Panamá e

seu canal. No final de “Garras de Oro”, o Tio Sam deposita esta mesma quantia

na balança da Justiça personificada, mas os pratos da balança não se movem:

afinal, a justiça deveria ser cega e mostrar que a razão sempre esteve com os

colombianos.

In English the film became known as “Dawn of Justice” because of its

cathartic content – a title that is more inoffensive than the two working titles

“Colombia’s Revenge” and “The Political Death of Teddy Roosevelt”. The US paid

Colombia 25 million dollars to Colombia as indemnity for Panama and its canal.

In the very end of “Garras de Oro”, Uncle Sam deposits the same amount in Lady

Justice’s scale, but the scale does not move: after all, Justice should be

blind and should show that the Colombians were right to be bitter.

Você lembra que todos os envolvidos com o filme “Garras de Oro” ou não

receberam crédito ou usaram pseudônimos? Agora a história se complica. Há uma

teoria que diz que “Garras de Oro” sequer foi filmado na Colômbia, mas sim na

Itália. Mais recentemente, a identidade do diretor PP Jambrina, também fundador

da Cali Films, foi descoberta: ele era Alfonso Martínez Velasco, um político,

jornalista e empresário. As únicas outras pessoas creditadas em “Garras de Oro”

são dois diretores de fotografia com sobrenomes italianos, e a atriz italiana

Lucia Zanussi pode ter sido parte do elenco. Assim como o nome dos outros

membros do elenco e o restante da trama, é possível que nunca saibamos a

verdade sobre o local de filmagem.

Do you remember that everyone involved in the making of “Garras de Oro”

was either uncredited or used pseudonyms? Now the plot thickens. A theory says

that “Garras de Oro” may not have been shot in Colombia at all, but in Italy.

More recently, the identity of director PP Jambrina, also founder of Cali

Films, was discovered: he was Alfonso Martínez Velasco, politician, journalist

and entrepreneur. The only other credited people in “Garras de Oro” were two

cinematographers with Italian last names, and Italian actress Lucia Zanussi is

rumored to be part of the cast. Just like the name of other cast members and

the rest of the plot, the place it was shot is something we might never know

for sure.

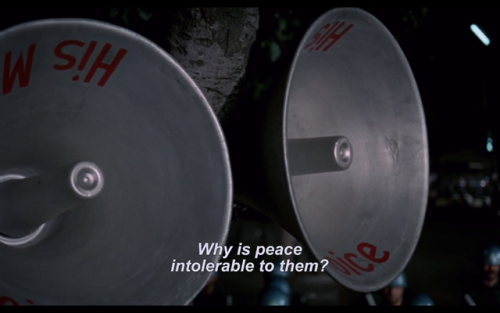

Durante o século XX, os EUA usaram o cinema como arma imperialista: por

todo o mundo, e na América Latina em especial, o cinema norte-americano

dominava e disseminava os valores norte-americanos. Hoje, este fenômeno é

irreversível, mas felizmente os EUA e Hollywood se abriram para as estrelas

latinas. Agora em Hollywood temos alguns colombianos fazendo sucesso, como

Sofía Vergara, Isabella Gomez e John Leguizamo. A animosidade causada por “Garras

de Oro” há quase 100 anos parece ter sido deixada no passado, mas temos sorte

porque parte do filme sobreviveu para contar uma história real sob uma

perspectiva única: do ponto de vista dos colonizados.

As the 20th century progressed, the US used cinema as a huge imperialist

weapon: all over the world, and in Latin America in special, US cinema

dominated and disseminated American values. Today, this phenomenon is

irreversible, but fortunately the US and Hollywood became more open to Latin

stars. Now in Hollywood we have a few Colombians thriving, like Sofía Vergara,

Isabella Gomez and John Leguizamo. The animosity caused by “Garras de Oro”

nearly 100 years ago seems to have been left in the past, but we’re lucky that

part of the film survives to tell a real story in such a unique perspective:

from the point of view of the colonized people.

This is my

contribution to the Hollywood’s Hispanic Heritage blogathon, hosted by Aurora

at Once Upon a Screen.